April 14, 1918, a roster of 14 personnel was officially submitted to the Office of the Chief Signal Officer and the 28th Infantry Division Pigeon Detachment was born.

"Wired communications and human messengers proved vulnerable to disruptions due to artillery fire," said Dr. Frank A. Blazich, Jr., Curator, Military History Division, National Museum of American History. "Pigeons became a reliable means of communication between the front and command posts."

Blazich authored, Feathers of Honor: U.S. Army Signal Corps Pigeon Service in World War I, 1917-1918. In his research he emphasizes the importance of the pigeon service. None are more famous than the pigeon, Cher Ami, and the Lost Battalion of the 77th Infantry Division.

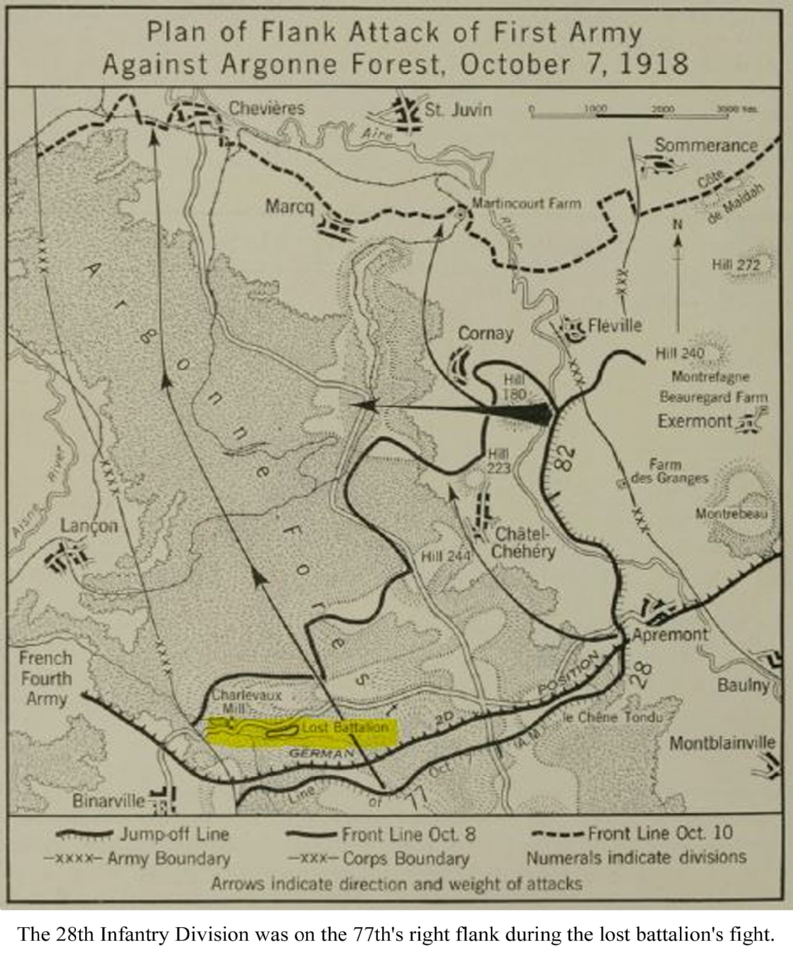

The story of the Lost Battalion includes the 28th Infantry Division who was poised on the right flank to aide in operations to relieve the battalion (see map).

In October 1918, the 77th Division advanced rapidly in France’s Argonne Forest and was ahead of adjacent forces on its flanks. The unit found itself surrounded and became known as the Lost Battalion. Trapped and cut off for almost a week, they were forced to rely on homing pigeons for communication.

Maj. Charles W. Whittlesey, commanding, sent seven messages from Oct. 3-4. His last pigeon was released at 3 p.m., Oct. 4, and arrived back one hour and 15 minutes later. The bird, named Cher Ami, was wounded but delivered the critical message that gave the exact location of the unit.

They were rescued the evening of Oct. 7, suffering nearly 70% causalities including their brave hero, Cher Ami, who passed later of wounds. The bird was taxidermized and is in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

The 28th Infantry Pigeon Detachment would have had operations like the 77th and they are outlined in the book: The Will to Communicate; A History of Pittsburgh’s 103rd Field Signal Battalion.

Division Headquarters had a loft with 96 pigeons and a team of 14 handlers assigned with one alternate. Each forward battalion would have 12 birds dedicated to them and broke out in three teams A, B and C. Four birds at the battalion command post (CP) was the A team, then B and C acted as relief on rotation at or near the division loft. Companies that had a need during operations would also receive birds if they were available.

Forty-eight birds were dedicated to the 53rd Artillery Brigade supporting the 28th Infantry Division. Observers would get 12 pigeons each to assist in call for fire.

| "Pigeon stations will be established at forward battalion P.C’s [command post reference]. Pigeons will be sent up to battalion P.C.’s every 48 hours by Signal Corps Supply. Those replaced will be released. Precautions must be taken to see that pigeons are protected from gas. Pigeons will be supplied by Division Signal Officer as soon as available.” – 28th Infantry Division, Field Order 41, Muse-Argonne Offensive |

The history of pigeons in military service is of interest to people today. As we take for granted our ability to message and the advanced technology of our time, people are fascinated by the feathered soldiers.

Blazich said the National Museum of American History has four stuffed birds from both world wars in its collection and that was part of his interest in studying them.

"Ever since 2018 I have kept researching and finding yet more fun elements to the birds and their usage in war," said Blazich. "I think the public loves the war animals because there is an innocence to animals serving humans in the worst of conditions. Also, animals are something slightly less ugly than the utter ugliness of war. Children to adults can appreciate and understand animals more than they can the insanity which is war."

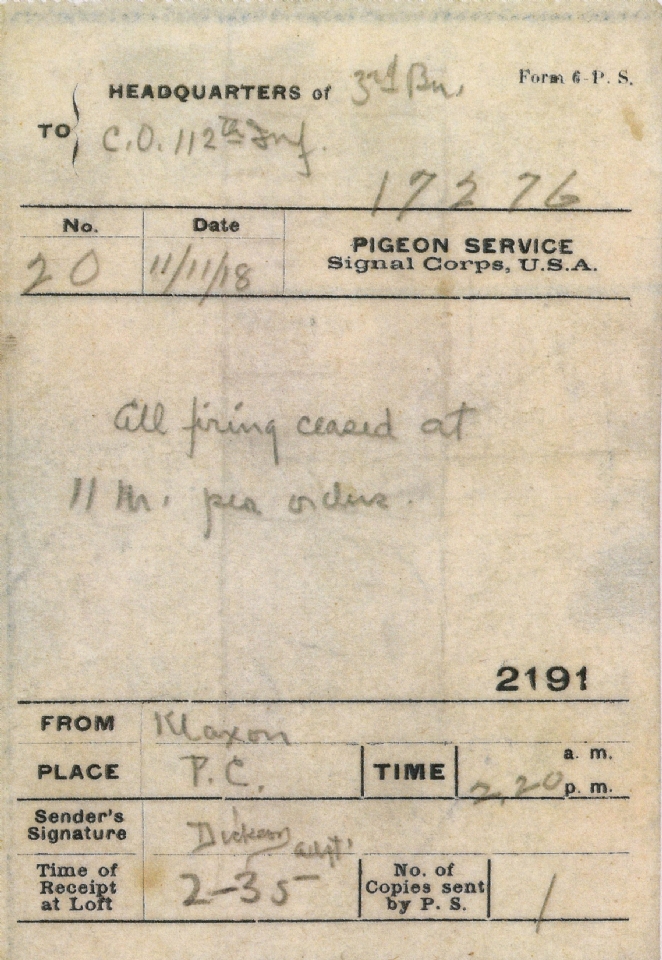

This pigeon message was sent by the 112th Infantry on Nov. 11, 1918, confirming that firing had ceased at 1100 hours. It is communicating the end of WW I. It is currently located at the Fort Indiantown Gap Military Museum.

Two bird assault basket carried by a Soldier at the front, 2nd Corps, Signal School, Chatillon sur Seine, Cote D’Or, France, Nov. 10th, 1918. Photo Courtesy of the USAHEC, World War I Misc. Roy Coles Album 3.

A pigeon handler shows the wing stamp used to positively identify a bird. Photo by Sgt. Warner, Signal Corps, Oct. 31, 1919. National Archives, Photographs of American Military Activities, between ca. 1918–ca. 1981.Local ID: 111-SC-67226

A pigeon handler shows the wing stamp used to positively identify a bird. Photo by Sgt. Warner, Signal Corps, Oct. 31, 1919. National Archives, Photographs of American Military Activities, between ca. 1918–ca. 1981.Local ID: 111-SC-67226